Introduction to access and benefit-sharing of genetic resources

November 9, 2017 - Categorised in: Opinions -This article is part of the Environmental Justice MOOC (free online course) of the University of East Anglia: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/environmental-justice/

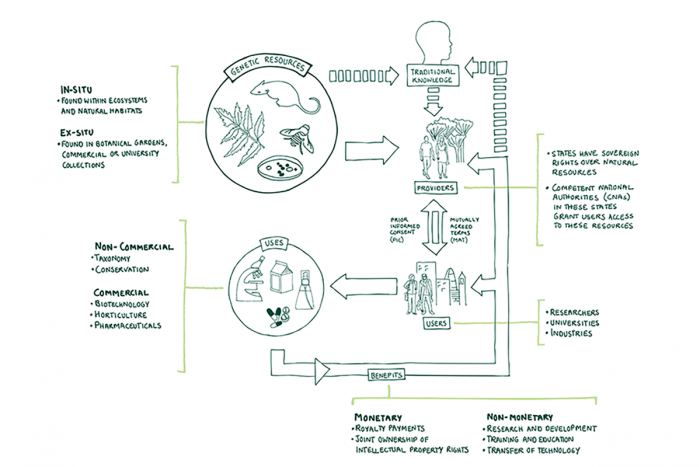

Access and Benefit-sharing, or ABS, refers to the set of principles used to organize the exchange of genetic resources between countries where they originate, and users of the resources (mostly commercial or non-commercial researchers).

As we have seen in the introductory video, many of these resources are sourced from the Global South but used in the Global North. The governance of ABS therefore is very interesting to illustrate the justice implications of biodiversity conservation, because the way in which they are accessed and the way in which people benefit from their use, involves issues of distribution, recognition and participation.

Genetic resources are all the living organisms (plants, animals and microbes) that carry genetic material that is of potential value to humans. You may not always be aware of this, but genetic resources are part of your day-to-day life. They are the raw material of many of the products developed by the biotechnology industry.

Chances are that the shampoo you have used this morning contained certain extracts or oils from plants originating somewhere in the Global South, from the plains of Africa to the rainforests in Asia and South-America.

This situation can be responsible for distributive injustices: people and countries using genetic resources reap most of the benefits, while the costs related to the conservation and protection of these same resources are mainly carried by provider countries. This is why, in 1992, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, or CBD, adopted the ‘fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources’ as its third objective. It was the first time concepts like ‘fairness’ and ‘equity’ were so central to a multilateral environmental agreement. Since then, the 2010 Nagoya Protocol has further specified and formalized the third objective of the CBD.

The CBD and its protocols, however, do not define terms such as ‘equity’ and ‘justice’. When exchanging genetic resources the question hence arises on what exactly constitutes ‘fair and equitable’ ABS. Answering this requires linking the concept of ABS to particular justice principles.

Let us use an example to illustrate this. Say you are a researcher for a European pharmaceutical company. For the development of a new drug regulating the absorption of glucose for type 2 diabetes patients, you are willing to use plant extracts originating in Ugandan forests.

You first need to be allowed access to the plant by the relevant authority. While the CBD reaffirms the ‘sovereign rights’ of the Ugandan State over its natural resources, local communities have been using the plant, which grows on their ancestral lands, for many generations. What is more, it was the existence of traditional knowledge that drew your attention to the potential benefits of that particular plant in the first place.

Who should have a say in granting you access: the local community, because they have always been using it? The State, which enjoys sovereign rights of the resource? Any external actors maybe: Ugandan citizen? Local or international NGOs? International institutions? This is where issues of participation come in.

Next, once you have been allowed access to the plant, the Nagoya Protocol asks you to establish a ‘benefit-sharing agreement’ stating the conditions of use and the way in which potential benefits will be shared and with whom. Some of the ways of distributing benefits are: shared equally; shared in a way that benefits the poor; shared according to incurred costs or efforts; or shared in a way that provides the greatest benefits for the greatest number of people. This is where issues of distribution come in.

Note that the above justice concerns, however legitimate, already frame the issues within certain conceptions of justice. These concerns deal with issues of ownership, property and monetization, concepts which are central to Western culture and capitalism.

But what if the problems lie ahead of this? What if injustices are produced by the very way in which the issues are framed? What if the mere fact of using the resources in a commercial way, hence exploiting nature and putting a price on it, is contradictory to the way in which a local community views nature? These types of questions lead us into the realm of recognition, introduced in this article.

Brendan Coolsaet

© University of East Anglia