Conservation works better when local communities lead it, new evidence shows

November 14, 2021 - Categorised in: Opinions -by Neil Dawson, Brendan Coolsaet, Julián Idrobo

We are currently facing a mass extinction of plants and animals. To remedy this, world leaders have pledged a huge expansion of protected areas ahead of the UN biodiversity summits to be held in October 2021 and May 2022 in Kunming, China.

The focus on how much of the planet to conserve overshadows questions of how nature should be conserved and by whom. In the past some conservation organisations have seen indigenous and local communities as undermining environmental conservation.

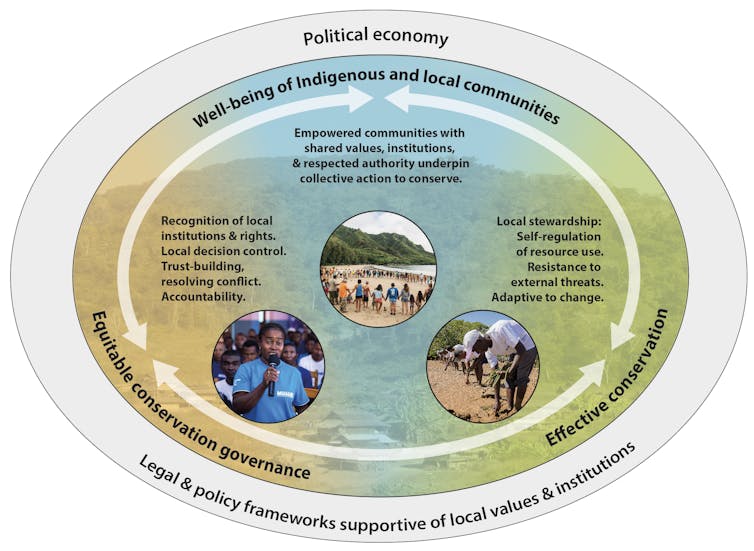

Our research strongly contradicts this. Our recent publication in Ecology and Society shows the best way to protect both nature and human wellbeing is for indigenous and local communities to be in control. That conclusion stems from examining examples of conservation projects carried out since 2000 and their results. Our international team of 17 scientists studied the effects on habitats and species and local communities.

We found improvements for conservation and people are much more likely when indigenous and local communities are environmental stewards. When in charge, local communities can establish a shared vision for conserving the environments they live in and for coexisting with wildlife. We show that applying their knowledge and ways of managing habitats and species is far more effective at protecting nature than efforts controlled by outside organisations.

Locals do it better

For example in southwest Taiwan, indigenous Tsou villagers took over conservation activities in a state-protected forest. After the community was put in charge, poaching and illegal logging greatly reduced. This success story has become a model for other communities in Taiwan.

Another example involved local communities in the western Brazilian Amazon protecting nests of the giant Amazon river turtle. Informal guards from local communities along the Juruá river reduced poaching levels to only 2% of nests – compared to 99% elsewhere, including in state-run protected areas.

In stark contrast, only a small minority of the projects led by states, international NGOs or companies enhanced both conservation and local people’s lives. We found a third of those initiatives run by outsiders were detrimental for both local people and nature. Those outsider-run approaches frequently fail because managers lack the money and personnel to enforce rules introduced without local consent. Offering small financial incentives or a seat at meetings is rarely enough to obtain approval and avoid local resistance.

In one of many examples, protected areas run by the Tanzanian government in the Serengeti for tourist safaris brought major financial gain for the state, but little for local people. Local people felt unfairly treated as they also lost access to grazing land and, in some cases, clean water. As a result of feeling excluded, locals no longer guarded their lands and illegal hunting increased.

However, there can be obstacles for local people in taking charge of projects. For example, in northwest California, historic discrimination against the indigenous Yurok has eroded local forest management organisations and knowledge. This community eventually won back control of its territory through the courts, but years of unchecked gold mining and timber extraction had caused considerable forest loss.

Fairer conservation

Supporting local communities’ rights to influence decisions about their lives, cultures and environments should not be viewed as a radical approach. Underestimation of local knowledge and practices by funders, governments and organisations who dominate conservation is counterproductive and discriminatory. There has been a gradual shift in policy towards recognising the role of indigenous and local communities, although this has not yet become mainstream conservation practice. The UN biodiversity summit must ensure a central role for indigenous and local communities or there will be another decade of well-meaning efforts that simply lead to further ecological decline and social harm.

There are reasons for optimism: we know conservation can become more effective through reinforcing the rights of indigenous and local communities. Examples include a declaration in Canada of more than 25 new protected areas which will follow indigenous stewardship principles.

If this bold direction were followed across the world, it could usher in a new era of local stewardship that greatly enhances the prospects for both people and nature.

Originally published on The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/conservation-works-better-when-local-communities-lead-it-new-evidence-shows-167425

Comments are closed here.